How Corrugated Steel Pipe Became Part of a Mysterious Native Legend

After working as a corrugated steel pipe specialist in the field of earth and water management industry for more than forty years, when it came to stories from the field, I thought I had pretty much seen and heard it all. But that was before I met a man – let’s call him Dan – who recounted a most mysterious tale about the Kaska Dena people.

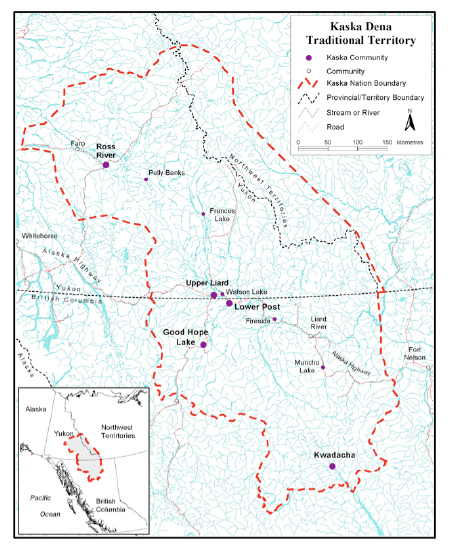

Dan is a resource road engineer and has supervised a lot of construction work within a 240-thousand square kilometer tract of land that extends from the southern Northwest Territories, through the southeastern boundary of the Yukon and into northern British Columbia. Long before recorded history or the existence of provincial land and territorial borders, the indigenous Kaska Dena people have lived here in harmony with nature, despite the land’s extreme climate and terrain.

Long before recorded history, the indigenous Kaska Dena people have lived

in this 240-thousand square kilometer area, in complete harmony with nature.

According to Timothy W. Shire, of the North Central Internet News (NCIN or Ensign), the Dena have for ages struggled very successfully in one of the world’s most hostile climates to find ways and means of supporting themselves. They are exceptional hunters and make extremely efficient use of the animals they use to sustain themselves. To accomplish this, the Dena became a highly innovative and technological people, as there is no other way of living in such an environment.

It wasn’t until 1901 that fur traders – the area’s first non-native settlers – arrived at the confluence of Ross and Pelly Rivers, a location which had already been a Kaska Dena meeting place for more than ten thousand years. In 1920, oil had been discovered at Norman Wells and the field supplied petroleum products to regional communities and mining interests throughout the 1920s and 1930s; however, very little of historical note happened in this area until World War II.

In the early 1940s, the threat of Japan invading North America stimulated outside interest in accelerating the development of the Norman Wells oilfield. Its remote location was the factor that delayed interest and progress in developing the field. But, in 1942, under a joint Canol Agreement, the U.S. Army, Canada, and Imperial Oil drilled 60 wells, expanded the existing refinery, and constructed a road and pipeline through 2,500 km of near-impassible mountains and hostile terrain: the Canol Road, which terminated at Whitehorse, some 1000 km (620 miles) to the southwest, was one of the largest construction projects of World War II; during that period of road construction to support the war effort, the Americans also built the Alaska Highway.

In 1953, rich mineral and ore deposits were discovered in the area, spurring the development of several mines, including what became Canada’s largest lead/zinc mine. Throughout these periods of non-indigenous people flocking to the area in search of profits from the land’s bounty, the Kaska Dena steadfastly maintained their traditional beliefs and way of life, yet seemed to easily integrate with newcomers as working partners when they chose to do so.

Shire describes the Kaska as people that “tended to be quiet, almost secretive and, unlike the Tahltans who all spoke only English, the Kaska knew only minimal English. But the Kaska, and I suspect most Dena people, because of their isolation and the difficult environment in which they live, seem to have retained the main elements of their traditional culture.”

It was around 1970 that my source, Dan, worked in the area as an engineer and helped build access roads, during which time he worked closely with his Kaska Dena co-workers. They were, according to Dan, good friends and great workers, yet they still enthusiastically cherished their Dena heritage and were sometimes quite secretive about their ancient beliefs and customs, which they regard as sacred.

Dan of course respected that, but also wondered about a very unusual and strange Kaska phenomenon rumoured to have been witnessed repeatedly by local, non-Kaska residents. Despite being dependable, hard working and forthright people, after every significant rainfall, many of their Kaska co-workers would mysteriously disappear and be absent for days, without explanation.

Dan couldn’t help but wonder, was this an ancient and secret tradition of sorts, being kept alive by the Kaska, but too sacrosanct a ritual to share with anyone outside of their own people? Perhaps it was a religious ceremony offering thanks to the almighty for the heaven-sent gift of rain to support ongoing life for all the earth’s plants and creatures? Maybe precipitation was a portent or forewarning for the Kaska peoples to respond with the same secret and hallowed actions as their forefathers had done since time immemorial.

When questioned, the Kaska Dena steadfastly refused to explain their absences, or even to share any clues regarding the nature of their mission. Inevitably, in light of this secrecy, curiosity fueled many rumors to explain this strange and esoteric behaviour.

One such rumor speculated that, during the post-rainfall periods, settlers had witnessed a group of absentee Kaska congregating around one of the area’s many corrugated steel pipe culverts. These corrugated steel culvert pipes were installed during road construction to facilitate uninterrupted and controlled passage of ubiquitous streams and creeks across the many local resource and service roads. Mysteriously, according to the rumor, the Kaska group would remain at the culvert site for a few hours, then move to the next corrugated steel pipe culvert, where they would repeat their actions and again move to another culvert site.

As with any unsubstantiated rumour, speculation abounded. One clever theory postulated that following a significant rainfall, the rapid movement of stream waters swelled by rain in higher ground cascaded downwards carrying abundance of eclectic marine life, including fish – a staple of the Kaska diet – and that the absentee Kaska were merely following the self-evident maxim that advises one should “fish where the fish are.” According to Dan, that had at first seemed a plausible explanation to the phenomenon.

Of course as a resource road engineer, Dan understood that all culverts serve as conduits for much more than just water; because streams also carry fish and wildlife along their corridors, culvert must not block the movement of these precious wildlife resources. However, in addition to encouraging the safe passage of fish and wildlife through steel culverts, corrugations effectively slow the velocity of flowing water along the walls of the corrugated steel pipe. In slowing water flow, corrugations encourage water borne dense particulate matter to precipitate and settle, forming a more natural streambed within the culvert, thereby facilitating easier passage for migrating fish and other aquatic life.

Nevertheless, as far as Dan was concerned, the rumoured ‘fishing’ explanation of this Kaska behaviour simply didn’t hold up to scrutiny, as there would have been no reason for them to be secretive about simply fishing.

Again, as a resource road engineer, Dan knew that, in addition to being wildlife friendly, corrugated steel pipes enable the safe passage of things – other than fish and aquatic wildlife – to be carried through it by the force of the moving water. So, pretty much anything small enough to fit through its opening – inanimate or living – can traverse and exit a culvert. In fact, corrugated steel pipe is often designed and specified with such unintended waterborne hitchhikers in mind.

So Dan started thinking about how the force of watersheds originating from high up in mountains easily washes down a myriad of passive hitchhikers, including abrasive sands, gravels and even boulders. And how, when propelled by gravity, fast flowing water can significantly abrade stream beds and banks.

Those thoughts were followed by his epiphany: mineral deposits from higher ground would also be washed quickly down the mountain by swollen rivers, streams and creeks. And when those rushing waters reached each resource road and entered a length of corrugated steel pipe culvert to traverse it, the slowing of the water flow effected by the interior corrugations of the pipe wall served as a catalyst enabling gravity to do its job to pull those dense particulates, such as sand and minerals, to the bottom and settle. Of course, the denser the particulate matter, the more likely it would end up as sediment. And what, thought Dan, were the densest local resources to have been discovered and mined in the area?

Suddenly it struck him – the most dense of all the region’s minerals was… GOLD! It turns out that, indeed, one of the heaviest burdens borne by streams the Kaska secretly visited was in fact gold. A few hundred dollars worth of dust and nuggets collects in and around corrugated steel pipe culverts after every storm, while lighter materials, as when panning for gold, continue on their way, downstream.

It has long been common knowledge that the Kaska were extraordinarily adept at reading clues in nature that lead them to discover valuable mineral ore deposits; in fact, in 1953, rich mineral deposits had been discovered in the area –discoveries which began a 20-year period of exploration and development. That same year, Dena Elders first reported finding streams of unusual colour, which eventually led a noted area prospector to locate significant ore bodies. A mere coincidence? Hardly.

So, it seems the gold waits for those who have spent several thousand years learning to read the land.